Meteorites and Mass Extinctions

Metorities and Mass Extinctions

go back to Contents of Entire Course...

Definitions

Composition and Classification

of Meteorites

Origin of Meteorites

Impact Events

Cratered Surfaces

Meteorite Impacts and Mass

Extinctions

Geologic Record of Mass

Extinction

Human Hazards

Torino Scale

...see also Meteorites

...see also

Minerals in Meteorites

...see

also Identifying Meteorites

...see also

Meteorite Cratering on Earth

...see

alsoTektites - Australia's unusual meteorite

...see also

The Tunguska Event - eyewitness reports translated into English

based on the lecture notes of Prof. Stephen A. Nelson, Tulane University adapted to HTML

Definitions

A Meteorite is a piece of rock from outer space that strikes the surface of the Earth. A Meteoroid is a meteorite before it hits the surface of the Earth. Meteors are glowing fragments of rock matter from outside the Earth's atmosphere that burn and glow upon entering the Earth's atmosphere. They are more commonly known as shooting stars. Some meteors, particularly larger ones, may survive passage through the atmosphere to become meteorites, but most are small objects that burn up completely in the atmosphere. They are not, in reality, shooting stars. Fireballs are very bright meteors. Meteor Showers - During certain times of the year, the Earth's orbit passes through a belt of high concentration of cosmic dust and other particles, and many meteors are observed. The Perseid Shower, results from passage through one of these belts every year in mid-August.

Throughout history there have been reports of stones falling from the sky, but the scientific community did not recognize the extraterrestrial origin of meteorites until the 1700s. Within recent history meteorites have even hit humans-

- 1938 - a small meteorite crashed through the roof of a garage in

Illinois

- 1954 - A 5kg meteorite fell through the roof of a house in Alabama.

- 1992 - A small meteorite demolished a car near New York City.

Composition and Classification of Meteorites

Meteorites can be classified generally into three types:

- Stones - Stony meteorites resemble rocks found on and within the

Earth. They are the most common type of meteorite, although because

they resemble Earth rocks they are not commonly recognized as

meteorites unless someone actually witnesses their fall. Stony

meteorites are composed mainly of the minerals olivine, and

pyroxene. Some have a composition that is roughly equivalent to

the Earth's mantle. Two types are recognized:

- Chondrites - Chondrites are the most common type of stony

meteorite. They are composed of small round glassy looking

spheres, called chondrules, that likely formed from condensation

from the gaseous solar nebula early in the history of the

formation of the solar system. Most chondrites have

radiometric age dates of about 4.6 billion years.

- Achondrites - Achondrites are composed of the same minerals as

chondrites, but lack the chondrules. They appear to have been

heated, melted, and recrystallized so that the chondrules are no

longer present. Most resemble volcanic rocks found on the

Earth's surface.

- Chondrites - Chondrites are the most common type of stony

meteorite. They are composed of small round glassy looking

spheres, called chondrules, that likely formed from condensation

from the gaseous solar nebula early in the history of the

formation of the solar system. Most chondrites have

radiometric age dates of about 4.6 billion years.

- Irons - Iron meteorites are composed of alloys of iron and nickel. They are easily recognized because they have a much higher density than normal crustal rocks. Thus, most meteorites found by the general populace are iron meteorites. When cut and polished, iron meteorites show a distinct texture called a Widmanstätten pattern (see figure 10.5, p. 254 in your text). This pattern results from slow cooling of a once hot solid material. Most researchers suggest that such slow cooling occurred in the core of much larger body that has since been fragmented. Iron meteorites give us a clue to the composition of the Earth's core.

- Stony Irons - Stony iron meteorites consist of a mixture of stony

silicate material and iron. Some show the silicates embedded in

a matrix of iron-nickel alloy. Others occur as a breccia, where

fragments of stony and iron material have been cemented together by

either heat or chemical reactions.

Origin of Meteorites

Most meteorites appear to be fragments of larger bodies called parent bodies.These could have been small planets or large asteroids that were part of the original solar system. There are several possibilities as to where these parent bodies, or their fragments, originated.

- The Asteroid Belt

The asteroid belt is located between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. It consists of a swarm of about 100,000 objects called asteroids. Asteroids are small rocky bodies with irregular shapes that have a cratered surface. About 4,000 of these asteroids have been officially classified and their orbital paths are known. Once they are so classified they are given a name.

The Asteroids as Parent Bodies of Meteorites

Much evidence suggests that the asteroids could be the parent bodies of meteorites. The larger ones could have differentiated into a core, mantle, and crust.

Fragmentation of these large bodies would then have done two things: First the fragments would explain the various types of meteorites found on Earth - the stones representing the mantle and crust of the original parent body, the irons representing the cores, and the stony irons the boundary between the core and mantle of the parent bodies. Second, the collisions that caused the fragmentation could send the fragments into Earth-crossing orbits.

Some of the asteroids have orbits that bring them close to Earth.

These are called Amor objects. Some have orbital paths that cross the orbital path of the Earth. These are called Earth-crossing asteroids or Apollo objects. All objects that have a close approach to the Earth are often referred to as Near Earth Objects or NEOs. About 150 NEOs with diameters between 1 and 8 km are known, but this is only a fraction of the total number. Many NEOs will eventually collide with the Earth. These objects have unstable orbits because they are under the gravitational influence of both the Earth and Mars. The source of these objects is likely the asteroid belt.

- Comets as Parent Bodies of Meteorites A Comet is a body that orbits around the Sun with an eccentric orbit. These orbits are not circular like those of the planets and are not necessarily within the same plane as the planets. Most comets have elliptical orbits which send them to the far outer reaches of the solar system and back toward a closer approach to the sun. As a comet approaches the sun, solar radiation generates gases from evaporation of the comet's surface. These gases are pushed away from the comet and glow in the sun light, thus giving the comet its tail. While the outer surface of comets appear to composed of icy material like water and carbon dioxide solids, they likely contain a more rocky nucleus. Because of their eccentric orbits, many comets eventually cross the orbit of the Earth. Many meteor showers may be caused by the Earth crossing an orbit of a fragmented comet.

The collision of a cometary fragment is thought to have occurred in the Tunguska region of Siberia in 1908. The blast was about the size of a 15 megaton nuclear bomb. It knocked down trees in an area about 850 square miles, but did not leave a crater. The consensus among scientists is that a cometary fragment about 20 to 60 meters in diameter exploded in the Earth's atmosphere just above the Earth's surface. Only small amounts of material similar to meteorites were found embedded in trees at the site.

Other Sources

While the asteroid belt seems like the most likely source of meteorites, some meteorites appear to have come from other places. Some meteorites have chemical compositions similar to samples brought back from the moon. Others are thought to have originated on Mars. These types of meteorites could have been ejected from the Moon or Mars by collisions with other asteroids, or from Mars by volcanic eruptions.

Impact Events

When a large object impacts the surface of the Earth, the rock at the site of the impact is deformed and some of it is ejected into the atmosphere to eventually fall back to the surface. This results in a bowl shaped depression with a raised rim, called an Impact Crater. The size of the impact crater depends on such factors as the size and velocity of the impacting object and the angle at which it strikes the surface of the Earth. Meteorite Flux and Size

Meteorite flux is the total mass of extraterrestrial objects that strike the Earth. This is currently about 107 to 109 kg/year. Much of this material is dust-sized objects called micrometeorites. The frequency at which meteorites of different sizes strike the Earth depends on the size of the objects, as shown in the graph below. Note the similarity between this graph and the flood recurrence interval graphs we looked at in our discussion of flooding.

Tons of micrometeorites strike the Earth each day. Because of their small size, they do not usually burn up when entering the Earth's atmosphere, but instead settle slowly to the surface. Meteorites with diameters of about 1 mm strike the Earth about once every 30 seconds. Upon entering the Earth's atmosphere the friction of passage through the atmosphere generates enough heat to melt or vaporize the objects, resulting in so called shooting stars. Meteorites of larger sizes strike the Earth less frequently. If they have a size greater than about 2 or 3 cm, they only partially melt or vaporize on passage through the atmosphere, and thus strike the surface of the Earth.

Objects with sizes greater than 1 km are considered to produce effects that would be catastrophic, because an impact of such an object would produce global effects. Such meteorites strike the Earth relatively infrequently - a 1 km sized object strikes the Earth about once every million years, and 10 km sized objects about once every 100 million years.

Velocity and Energy Release of Incoming Objects

The velocities at which small meteorites have impacted the Earth range from 4 to 40 km/sec. Larger objects would not be slowed down much by the friction associated with passage through the atmosphere, and thus would impact the Earth with high velocity. Calculations show that a meteorite with a diameter of 30 m, weighing about 300,000 tons, traveling at a velocity of 15 km/sec (33,500 miles/hour) would release energy equivalent to about 20 million tons of TNT.

Such a meteorite struck at Meteor Crater, Arizona (the Barringer Crater) about 49,000 years ago leaving a crater 1200 m in diameter and 200 m deep. The amount of energy released by an impact depends on the size of the impacting body and its velocity. An impact like the one that struck the Yucatan Peninsula, in Mexico about 65 million years ago, thought responsible for the extinction of the dinosaurs and numerous other species, created the Chicxulub Crater, 180 km in diameter and released energy equivalent to about 100 million megatons of TNT.

For comparison, the amount of energy needed to create a nuclear winter on the Earth as a result of nuclear war is about 8,000 megatons, and the energy equivalent of the world's nuclear arsenal is about 60,000 megatons.

Cratered Surfaces

Looking at the surface of the Moon, one is impressed by the fact that most of the surface features of the moon are shaped by impact craters. The Earth is subject to more than twice the amount of impacting events than the moon because of its larger size and higher gravitational attraction. Yet, the Earth does not show a cratered surface like the moon. The reason for this is that the surface of the Earth is continually changing due to processes like erosion, weathering, tectonism, sedimentation, and volcanism. Thus, the only craters that are evident on the Earth are either very young, very large, or occurred on stable continental areas that have not been subject to intense surface modification processes. Currently, approximately 200 terrestrial impact structures have been identified, with the discovery rate of new structures in the range of 3-5 per year (see figure 10.15, page 262 in your text).

The Mechanics of Impact Cratering

When a large extraterrestrial object enters the Earth's atmosphere the initial impact with the atmosphere will compress the atmosphere, sending a shock wave through the air. Frictional heating will cause the object to heat and glow. Melting and even vaporization of the outer parts of the object will begin, but if the object is large enough, solid will remain when it impacts the surface of the Earth.

Impact of large meteorites have never been observed by humans.

Much of our knowledge about what happens next must come from scaled experiments. As the solid object plows into the Earth, it will compress the rocks to form a depression and cause a jet of fragmented rock and dust to be expelled into the atmosphere. This material is called ejecta. The impact will send a shock wave into the rocks below, and the rocks will be crushed into small fragments to form a breccia. Some of the ejecta will be hot enough to vaporize, and the heat generated by the impact could be high enough to actually melt the rock at the site of the impact. The shock wave entering the Earth will first move in as a compressional wave (P-wave), but after passage of the compressional wave an expansion wave (rarefaction wave) will move back toward the surface. This will cause the floor of the crater to be uplifted and may also cause the rock around the rim of the crater to bent upward. Faulting may also occur in the rocks around the crater, causing the crater to become enlarged, and have a concentric set of rings.

The ejecta will eventually settle back to the Earth's surface forming an ejecta blanket that is thick near the crater rim and thins outward from the crater. Rocks below the crater that were not melted by the impact will be intensely fractured. All of this would happen in a matter of 1 to 2 minutes.

Meteorite Impacts and Mass Extinctions

The impact of a space object with a size greater than about 1 km would be expected to be felt over the entire surface of the Earth. Smaller objects would certainly destroy the ecosystem in the vicinity of the impact, similar to the effects of a volcanic eruption, but larger impacts could have a worldwide effect on life on the Earth. We will here first consider the possible effects of an impact, and then discuss how impacts may have resulted in mass extinction of species on the Earth in the past. Regional and Global Effects

Again, we as humans have no firsthand knowledge of what the effects of an impact of a large meteorite or comet would be. Still, calculations can be made and scaled experiments can be conducted to estimate the effects. The general consensus is summarized here.

- Massive earthquake - up to Richter Magnitude 13, and numerous large magnitude aftershocks would result from the impact of a large object with the Earth.

- The large quantities of dust put into the atmosphere would block incoming solar radiation. The dust could take months to settle back to the surface. Meanwhile, the Earth would be in a state of continual darkness, and temperatures would drop throughout the world, generating global winter like conditions. A similar effect has been postulated for the aftermath of a nuclear war (termed a nuclear winter). Blockage of solar radiation would also diminish the ability of photosynthetic organisms, like plants, to photosynthesize. Since photosynthetic organisms are the base of the food chain, this would seriously disrupt all ecosystems.

- Widespread wildfires ignited by radiation from the fireball as the object passed through the atmosphere would be generated. Smoke from these fires would further block solar radiation to enhance the cooling effect and further disrupt photosynthesis.

- If the impact occurred in the oceans, a large steam cloud would be produced by the sudden evaporation of the seawater. This water vapor and CO2 would remain in the atmosphere long after the dust settles. Both of these gases are greenhouse gases which scatter solar radiation and create a warming effect. Thus, after the initial global cooling, the atmosphere would undergo global warming for many years after the impact.

- If the impact occurred in the oceans, giant tsunamis would be generated. For a 10 km-diameter object the leading edge would hit the seafloor of the deep ocean basins before the top of the object had reached sea level. The tsunami from such an impact is estimated to produce waves from 1 to 3 km high. These could easily flood the interior of continents.

- Large amounts of nitrogen oxides would result from combining Nitrogen and Oxygen in the atmosphere due to the shock produced by the impact. These nitrogen oxides would combine with water in the atmosphere to produce nitric acid which would fall back to the surface as acid rain, resulting in the acidification of surface waters.

Geologic Record of Mass Extinction

It has long been known that extinction of large percentages families or species of organisms have occurred at specific times in the history of our planet. Among the mechanisms that have been suggested to have caused these mass extinctions have been large volcanic eruptions, changes in climatic conditions, changes in sea level, and, more recently, meteorite impacts. While the meteorite impact theory of mass extinctions has become accepted by many scientists for particular extinction events, there is still considerable controversy among scientists. In this course we will accept the possibility that an impact with a large object could have caused at least some of the mass extinction events, as it would certainly seem possible given the effects that an impact could have, as discussed above. Still, because of their are many other possibilities for the cause of mass extinctions, please read your book for the arguments against the impact theory.

Major extinction events occurred at

- the end of the Tertiary Period, 1.6 million years (m.y.) ago.

- the end of the Cretaceous Period, marking the boundary between the Cretaceous and Tertiary periods 65 m.y. ago. (Geologists use the letter K to stand for Cretaceous Period and the letter T for the Tertiary Period. Thus this boundary is commonly called the K-T boundary).

- the end of the Triassic, 208 m.y. ago.

- the end of the Permian, 245 m.y. ago (estimated that over 96% of the species alive at the time became extinct).

- the end of the Devonian, 360 m.y. ago

- the end of Ordovician, 438 m.y. ago

- the end of the Cambrian period, 505 m.y. ago

The mass extinction at the end of the Mesozoic Era, that is the Cretaceous - Tertiary boundary (often called the K-T boundary) 65 million years ago, shows much evidence that it was related to an impact with an extraterrestrial object. This event resulted in the extinction of over 50% of the species living at the time, including the dinosaurs. In 1978 a group of scientist led by Walter Alvarez of the University of California, Berkeley, were able to locate the K-T boundary very precisely in layers of limestones near Gubbio, Italy. At the boundary they found a thin clay layer. Chemical analysis of the clay revealed that it contains an anomalously high concentration of the rare element Iridium (Ir). Ir has extremely low concentrations in most crustal rocks, however it reaches very high concentrations in meteorites. The only other possible source of high concentrations of Ir is basaltic magmas. Over the next several years, the K-T boundary was located at several other sites throughout the world, and also found to have a thin clay layer with high concentrations of Ir. Although a large eruption of basaltic magma could not immediately be ruled out as the source of the high concentration of Ir, other evidence began to accumulate that the fallout of impact ejecta had been responsible for both the thin clay layers and the high concentrations of Ir. Among the evidence found at different localities where the K-T boundary is exposed is:

- Clay layers at some localities have a high proportion of black carbon that could have originated as soot produced by wildfires set off by an impact.

- Some of the clay layers contain grains of quartz with a crystal structure that shows evidence that the quartz was severely strained by a large shock.

- In some clay layers tiny grains of the mineral stishovite is found. Stishovite is a high pressure form of SiO2 that is not found at the Earth's surface except around known meteorite impact sites. The mineral can only be produced as a result of extremely deep burial in the Earth, or by high pressure generated by an impact.

- Other clay layers contain tiny spherical droplets of glass, called spherules. The glass is not basaltic in composition, but could represent droplets of melt formed during an impact event.

At the time of these discoveries, there was no known impact structure on the Earth with an age of 65 million years.

This is not unexpected, since 71% of the Earth's surface is covered by water, and is largely unexplored. But, in the late 1980s attention started to be focused on a buried impact site near the tip of the Yucatan Peninsula, in Mexico. Here oil geologists had drilled through layers of brecciated rock and found impact melt rock. Further geophysical studies revealed a circular structure about 180 km in diameter. Radiometric dating reveals that the structure, called the Chicxulub Crater, formed about 65 million years ago.

Although the crater itself is now filled and buried by younger rocks, drilling throughout the Gulf of Mexico has revealed the presence of shocked quartz, glass spherules, and soot in deposits the same age as the crater. In addition, geologists have found deposits from the tsunami that was generated by the impact all along the Gulf of Mexico coast extending considerable distance inland from the current shoreline. The size of the crater suggest that the object that produced it was about 10 km in diameter. While there is still some debate among geologists and paloebiologists as to whether or not the extinctions that occurred at the K-T boundary were caused by the impact that formed Chicxulub Crater, it is clear that an impact did occur about 65 million years ago, and that it likely had effects that were global in scale. What would happen if another such event occurred while we humans dominate the surface of the Earth, and what could we as humans do, if anything to prevent such a catastrophic disaster?

Human Hazards

It should be clear that even if an impact of a large space object did not cause the extinction of humans, the effects would cause a natural disaster of proportions never witnessed by the human race. Here we first look at the chances that such an impact could occur, then look at how we can predict or provide warning of such an event, and finally discuss ways that we might be able to protect ourselves from such an event.

Risk - It is estimated that in any given year the odds that you will die from an impact of an asteroid or comet are about 1 in 20,000. The table below shows the odds of dying in the U.S. from various other causes. Although 1 in 20,000 seem like long odds, you have about the same odds of dying in an airplane crash, and somewhat less risk of dying from other natural disasters likes floods and tornadoes. In fact the odds of dying from an impact event are much better than the odds of winning the lottery.

| Odds of Dying in the U.S. from Selected Causes | |

|---|---|

| Cause | Odds |

| Motor Vehicle Accident | 1 in 100 |

| Murder | 1 in 300 |

| Fire | 1 in 800 |

| Firearms Accident | 1 in 2,500 |

| Electrocution | 1 in 5,000 |

| Asteroid or Comet Impact | 1 in 20,000 |

| Airplane Crash | 1 in 20,000 |

| Flood | 1 in 30,000 |

| Tornado | 1 in 60,000 |

| Venomous Bite or Sting | 1 in 100,000 |

| Food Poisoning by Botulism | 1 in 3,000,000 |

| Odds of winning the Lottery | 1 in 7,000,000 |

In March, 1989 an asteroid named 1989 FC passed within 700,000 km of the Earth, crossing the orbit of the Earth. It was not discovered until after it had passed through the orbit of the Earth. Its size was estimated to be about 0.5 km. Such a body is expected to hit the Earth about once every million years or so, and would release energy equivalent to about 10,000 megatons of TNT, a little greater than the energy released in a nuclear war, and enough to cause nuclear winter event (see graph above). Although 700,000 km seems like a long distance, it translates to a miss of the Earth by only a few hours at orbital velocities.

Torino Scale -

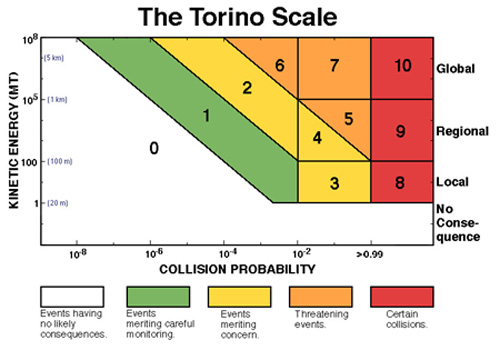

In order to develop a better means of communicating the potential hazards of a possible impact with a space object, scientists have developed a scale that describes the potential (see - http://neo.jpl.nasa.gov/torino_scale.html). The scale is called the Torino Scale, and is shown below.

| Events

Having No Likely Consequences (White Zone) |

0 |

The likelihood of a collision is zero, or well below the chance that a random object of the same size will strike the Earth within the next few decades. This designation also applies to any small object that, in the event of a collision, is unlikely to reach the Earth's surface intact. |

| Events

Meriting Careful Monitoring (Green Zone) |

1 |

The chance of collision is extremely unlikely, about the same as a random object of the same size striking the Earth within the next few decades. |

| Events

Meriting

Concern (Yellow Zone) |

2 |

A somewhat close, but not unusual encounter. Collision is very unlikely. |

3 |

A close encounter, with 1% or greater chance of a collision capable of causing localized destruction. | |

4 |

A close encounter, with 1% or greater chance of a collision capable of causing regional devastation. | |

| Threatening

Events

(Orange Zone) |

5 |

A close encounter, with a significant threat of a collision capable of causing regional devastation. |

6 |

A close encounter, with a significant threat of a collision capable of causing a global catastrophe. | |

7 |

A close encounter, with an extremely significant threat of a collision capable of causing a global catastrophe. | |

| Certain

Collisions

(Red Zone) |

8 |

A collision capable of causing localized destruction. Such events occur somewhere on Earth between once per 50 years and once per 1000 years. |

9 |

A collision capable of causing regional devastation. Such events occur between once per 1000 years and once per 100,000 years. | |

10 |

A collision capable of causing a global climatic catastrophe. Such events occur once per 100,000 years, or less often. |

For an object making a close approach to Earth, its categorization on the Torino Scale is dependent upon its placement within this plot showing kinetic energy versus collision probability. (One MT = 4.3 x 10^15 J.) The left-hand scale also indicates approximate sizes for asteroidal objects having typical encounter velocities. For an object that makes multiple close approaches over a set of dates, a Torino Scale value should be determined for each approach. It may be convenient to summarize such an object by the greatest Torino Scale value within the set.

- Prediction and Warning - It is estimated that over 90% of NEOs have not yet been discovered. Because of this, with our present knowledge, there is a good chance that the only warning we would have is the flash of light from the fireball as one of these objects entered the Earth's atmosphere. Scientists have proposed the "Spaceguard Survey" to find and track all of the large NEOs. If such a survey is carried out, we could predict the paths of all NEOs and have years to decades to prepare for an NEO that could impact the Earth.

- Mitigation - Impacts are the only natural hazard that we can prevent from happening by either deflecting the incoming object or destroying it. Of course, we must first know about such objects and their paths in order to give us sufficient warning to prepare a defense. Sufficient time is usually thought to be about 10 years. This would likely give us enough time to prepare a space mission to intercept the object and deflect its path by setting off a nuclear explosion. Currently, however, there are no detailed plans. But, even if we did not have the ability to destroy or deflect such an object, 10 years warning would provide sufficient time to store food and supplies, and maybe even evacuate the area immediately surrounding the expected impact site.