Offshore Oil Drilling

Offshore Oil Drilling

adapted to HTML from Australian Institute of Petroleum with permissionAustralia

Potential Traps

Environmental safeguards

Four drilling rig types

Production platforms

Drilling for oil

Drilling fluid

Drill cuttings

Produced formation water

Preventing "blow-outs"

Directional drilling

Completing the well

A dry well

see also Fuels..

see also Oil Spills...

see also Oil Refining...

see also Oil Deposits...

see also Marine Oil Exploration...

Drilling or digging for oil has occurred in one way or another for hundreds of years. The Chinese, for instance, invented a bamboo rig to obtain oil and gas for lighting and cooking.

Only recently has humankind been able to efficiently extract petroleum from beneath the seas - an achievement to rank with this century's mightiest technological triumphs.

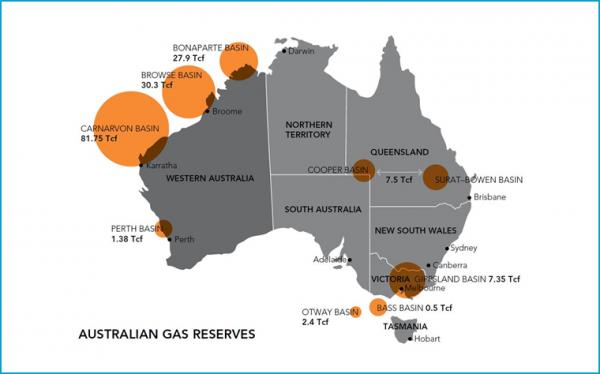

Australia

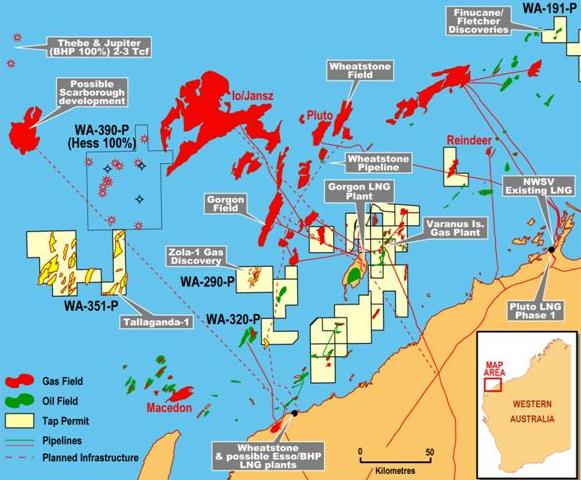

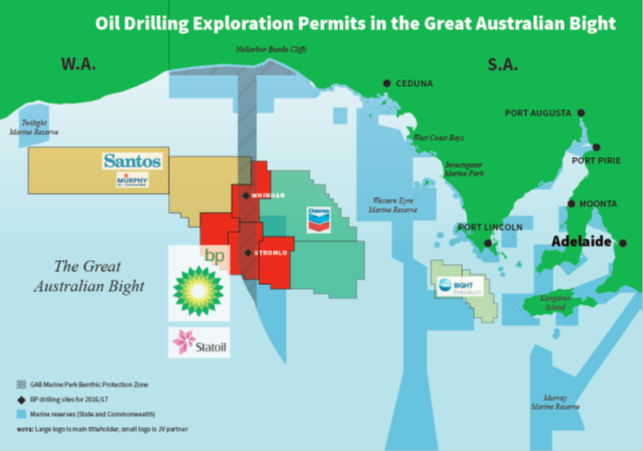

In Australia, nearly 90 per cent of our petroleum wealth is found offshore. The search is difficult, extremely expensive, and often fruitless - but critical to the nation's economic future.Locating an oil and gas "trap" - as it is known - and extracting the oil and gas is difficult enough on land. But offshore, in deep and often stormy waters, it becomes an awesome undertaking.

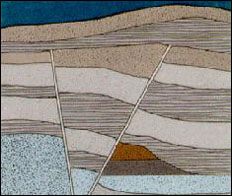

Potential Traps

Potential traps are identified by analysing seismic survey data but whether they contain oil or gas won't be known until a drill bit penetrates the structure. Directing the drill bit to a precise location - perhaps several kilometres away - requires sophisticated computer technology. A navigation device installed above the drill bit feeds back information which enables the exact position of the well to be measured and monitored. A steerable motor within the drill pipe can be remotely controlled to adjust the direction of the drill.Anticlinal Trap

Fault Trap

Environmental safeguards

What is the impact of drilling on the marine environment?The Australian offshore petroleum industry has always contended that its activities are environmentally friendly.

The industry's case has now been given increased strength with the findings of the Independent Scientific Review Committee (ISRC) inquiry commissioned by the Australian Petroleum Exploration Association.

In Australia up to 100 offshore wells per year are drilled. About a quarter of these are development wells to produce oil or gas found by previous drilling.

Before a well can be drilled, government approval must be obtained. Drilling must then conform to statutory conditions and further operations are covered by industry Codes of Practice.

The Independent Scientific Review has found that environmental impacts from offshore exploration and production are negligible. The ISR examined the potential environmental effects of discharge of drilling fluids, drill cuttings and "produced formation water" (PFW).

Companies in Australia safeguard the environment and minimise impacts in a number of ways.

Drilling fluids used in Australia are almost exclusively water-based, not oil-based.

During production, oil is separated from the water by mechanical devices before the produced formation water is returned to sea. Australia's regulations on how much petroleum hydrocarbon is contained in PFW are among the world's strictest.

Sophisticated and reliable blowout prevention systems (BOP) are used in every production well to minimise the possibility of a blowout - where uncontrolled fluids flow from a well.

Four drilling rig types

In the early days of offshore drilling, explorers simply fitted a derrick to a barge and towed it to their site. Today, four types of offshore rigs are used to drill wildcat or exploration wells.- Submersibles. These are rarely used. They can be floated to shallow water locations then ballasted to sit on the seabed.

- Jackups. Usually towed to a location. Their legs are then lowered to the seabed and the hull is jacked-up clear of the sea surface. Used in waters to about 160 metres deep.

- Drill ship. These look like ordinary ships but have a derrick on top which drills through a hole in the hull. Drill ships are either anchored or positioned with computer-controlled propellers along the hull which continually correct the ships drift. Often used to drill "wildcat" wells in deep waters.

- Semi submersible. Mobile structures, some with their own locomotion. Their superstructures are supported by columns sitting on hulls or pontoons which are ballasted below the water surface. They provide excellent stability in rough, deep seas.

Production platforms

Once oil or gas is discovered, the drilling rig is generally replaced by a production platform, assembled at the site using a barge equipped with heavy lift cranes.Platforms vary in size, shape and type depending on the size of the field, the water depth and the distance from shore. In Australia's medium to large fields, fixed production platforms are commonly used.

These are made of steel and fixed to the seabed with steel piles. These platforms house all the processing equipment and accommodate up to 80 workers who typically work a 12 hour day, one week on and one week off. There are also concrete structures which are big enough to store oil. Gravity holds them on the seabed.

The world's biggest platforms are bigger than a football field and rise above the water as high as a 25 storey office tower. They are home to 500 workers.

If the field is in shallow water and near land or another platform, small remotely controlled monopod platforms may be used. Another system is a floating structure, either anchored or tethered, called a Floating Production Storage Offloading (FPSO) vessel.

Another platform type, suitable for deep water production, is the Tension Leg platform, built of steel or concrete and anchored to the sea floor with vertical "tendons".

Drilling for oil

The first stage of drilling is called "spudding" and drilling starts when the drill bit is lowered into the seabed.

The bit can be of two types: - a roller cone or rock bit which usually has three cones armed with steel or tungsten carbide : teeth:; or buttons; or - a diamond bit, imbedded with small industrial diamonds.

The drill bit is attached to drill pipe (or a drill string) and rotated by a turntable on the platform floor. As the hole deepens, extra lengths of drill pipe are attached.

A length of drill pipe is 30 feet long, or 9.1 metres (oil workers use the old imperial measurement system). The drill bit ranges in diameter from 36 inches or approximately 91.4 centimetres (used at the start of the hole) to eight and a half inches (approximately 21.5 centimetres).

Drilling may take weeks or months before the targeted location is reached.

The major potential environmental effects from offshore drilling result from the discharge of wastes, including drilling fluids, drill cuttings and "produced formation water" (PFW).

Drilling fluid

Drilling fluid is pumped down the drill pipe and into the hole at high velocity through nozzles in the drill bit. The fluid is usually a mixture of water, clay, a weighting material (usually barite), and various chemicals.The drilling fluid serves several purposes. It raises the drill cutting to the surface for disposal; it provides the "weight" to keep the underground pressures in check; it keeps the hold stable by caking the wall with a thin layer of clay; and it cleans and cools the bit.

The fluid is recycled through a circulation system where equipment mounted on the drilling rig separates out the drill cuttings and allows the clean fluid to be pumped back down the hole. With few exceptions, Australian wells since 1985 have been drilled using water-based drilling fluids, not oil-based.

The ISRC concluded that "drilling waste discharges have generally been shown to have only minor effects on water quality and pelagic ecosystems".

Evidence collected by the ISRC suggests that acute toxic effects of drilling fluids on marine organisms are only found at very high concentrations. "Toxic effects on the biota in the water column from such concentrations would only be present within a few tens of metres from the point of discharge and only for short times after discharge".

As the plume of drilling fluid and cuttings falls to the seabed, it disperses, with 90 percent of it settling within 100 metres of the platform. Soluble waste concentrations will have fallen by a factor of 10,000 within 100 metres and suspended sediment concentrations by a factor of at least 50,000.

Drill cuttings

As the well is drilled, the "cuttings", consisted of crushed rock and clay, are brought to the surface by the drilling fluid and discharged overboard.New measures to reduce discharges such as re-injecting the cuttings into the well and slim hole drilling are being examined and tested by the industry.

Produced formation water

Where you find oil, you often also find water. As oil is drawn from a reservoir, it is therefore necessary to separate the water and return it to the ocean.This is what is known as "produced formation water" (PFW). Great emphasis is placed on ensuring that the water returned to the ocean is as free as possible from oil and chemicals. Strict regulations apply on how much petroleum hydrocarbon is contained in PFW. The Australian regulatory limit is 30 mg/litre average. Mechanical separation devices and chemical treatments are used to separate oil and water efficiently.

Preventing "blow-outs"

The weight of the drilling fluid acts as the first line of well control by keeping underground pressures in check. If an influx of pressurised oil or gas does occur during drilling, well control is maintained through the rig's blowout prevention system (BOP). This is a set of hydraulically operated valves and other closure devices (rams) which seal off the well, and route the wellbore fluids to specialised pressure controlling equipment.Trained personnel operating this highly reliable equipment minimise the possibility of a "blowout", or an uncontrolled flow of fluids from a well.

Directional drilling

Drilling an oil well may not be a case of going straight down. Directional drilling has been developed where drill bits are steered laterally over a distance of up to several kilometres towards the petroleum reservoir.One production platform is often used to drill a number of wells, in a variety of directions and inclinations. To steer the drill bit, a downhole motor may be used. It is turned by pumping the drilling mud through it.

Completing the well

When the well has been drilled to its target depth, production casing is set and cemented.Tubing is lowered into the hole together with "packers" which seal the space between the tubing and the casing. Finally, at the end of the well, the casing is perforated at predetermined depths by small explosive charges detonated remotely. The small holes in the casing allow the oil or gas under its natural pressure to flow to the surface.